Key Points

- The U.S. mutual fund business operates in a highly competitive financial services market. The

600 organizations that offer mutual funds compete among themselves and with other investment

services and products. - Three types of pressures stand out as drivers of mutual fund competition. The 90 million fund

shareholders’ demand for investment performance and services at a competitive level of fees and

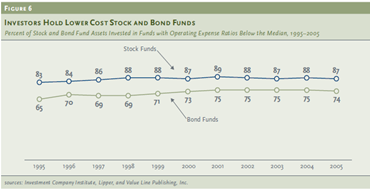

expenses continually impacts mutual funds. - Mutual fund shareholders are heavily invested in lower-cost funds with above-average, long term

performance. More than three-quarters of stock and bond fund assets are invested in funds

charging below-average operational and management expenses; nearly two-thirds of stock and

bond fund assets are held in funds with above-average, 10-year performance records.

A Large Number of Mutual Fund Sponsors Compete for Investors

The U.S. market for mutual funds is highly competitive

and dynamic and provides strong market incentives

that reward or discipline fund sponsors based on their

ability to meet their shareholders’ investment and

service needs and demands.

More than 600 fund organizations offer funds

that manage investors’ assets, and fund investors can

redeem their shares in a fund at any time, requiring

fund sponsors to continually compete with one another

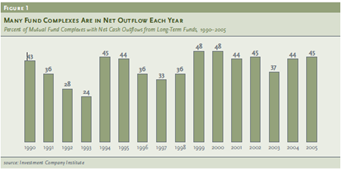

to retain and attract investors. In 2005, for example,

shareholders redeemed about one-quarter of their

stock and bond mutual fund assets and, in every year

since 1990, between one-quarter and one-half of fund

sponsors experienced net outflows from their long term

funds (Figure 1).

Mutual funds not only compete among themselves

for investors, they also compete with other investment

services and products. Mutual funds manage about 20

percent of household fi nancial assets. Investors and

their fi nancial advisers can also choose to invest in

bank deposits, insurance products, separately managed

accounts, direct holdings of stocks and bonds, hedge

funds, real estate investment trusts, exchange-traded

funds, and other investment products.

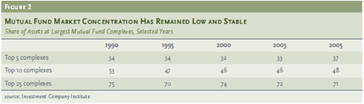

The large number of fund sponsors and the

dynamic nature of the financial services market have

kept market concentration of the largest fund sponsors

stable for the past 15 years. For example, in 1990,

the 10 largest mutual fund sponsors managed 53

percent of mutual fund assets; in 2005, the 10 largest

firms managed 48 percent of the assets (Figure 2).

Competition and other market dynamics have also

altered the rankings among fund companies, such

that many funds once ranked among the largest

firms no longer exist or have fallen in their assets under-

management ranking. Of the 10 largest mutual

fund sponsors in 1990, five were not ranked among the

top 10 in 2005.

Shareholders Place Competitive Pressures on Funds

Approximately 90 million investors, with a wide range

of financial objectives and service needs, currently

own mutual fund shares. These shareholders can

use a variety of resources to choose the funds that

best meet their investment goals and service needs.

For example, funds provide a large amount of

information — available through disclosure documents,

media sources, online search tools, and fund

web sites—that helps investors select funds.

Fund shareholders often receive additional

assistance in processing this information when

selecting funds. Nearly two-thirds of all fund

shareholders invest in mutual funds through retirement

plans at work, and employers sponsoring these plans

rely on this information to choose the funds and

other investments that they offer to their employees.

Among shareholders who own funds outside of work

retirement plans, 80 percent use financial advisers, who

help investors identify the funds or other investments

that best meet their financial goals.

Competition, in general, drives firms to

innovate and thereby differentiate themselves in the

marketplace. This differentiation can take the form

of fees, service, and other factors that allow funds to

target particular groups or types of investors. Over

time, however, shareholders reward funds that are

best able to deliver performance and service at a

competitive level of fees.

Pressure to Compete through Performance.

Shareholder demand for performance is one of

the most widely documented competitive forces.

Numerous academic papers have demonstrated that

the best performing funds receive most of the net

new cash flow.1 Moreover, mutual fund assets are

concentrated in long-established funds with above average

performance histories.

Investors, with the help of their financial advisers

and retirement plan sponsors, appear to favor long tenured

funds. From one year to the next, investors

have held roughly three-quarters of their stock and

bond fund assets in funds that have operated for at

least 10 years (Figure 3). Fund shareholders’ tendency

to invest in these funds is striking because during the

past two decades there has been tremendous growth in

the creation of new funds to meet the growing investor

demand. In fact, only 10 to 20 percent of all stock and

bond funds in any given year since the mid-1990s have

been open for a decade or longer

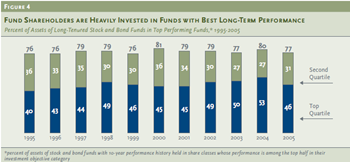

When shareholders choose among funds with

long performance records, they favor those funds that

have the best long-term performance. Those stock

and bond mutual funds ranked among the top half

of their peers, as measured by 10-year performance,2

manage more than three-quarters of the assets held by

funds with performance histories of 10 years or longer

(Figure 4). Taking together investors’ preference for

long-tenured funds with above-average performance,

investors held nearly two-thirds of all of their stock and

bond fund assets in funds with above-average, 10-year

performance records.

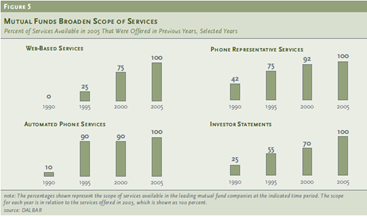

Pressure to Compete with Service Innovation.

Shareholders also pay close attention to fund services.

Mutual funds offer a broad range of services as

competition drives them to innovate and offer new

and better services. For example, fund organizations

typically maintain elaborate web sites that provide

current and prospective investors with information

about mutual funds and investing, and upgrade

their web sites with information and services not

available 15 years ago (Figure 5).3 Fund companies

have also significantly expanded the scope of other

shareholder services, including information provided

on shareholder statements and via the telephone.

Other, more tailored services appeal to particular

groups of investors. Walk-in offices in multiple

locations serve shareholders that prefer the option of face-to-face contact with fund service personnel.

Many shareholders use a financial adviser when buying

funds, and fund organizations offer share classes

designed for investors who choose to employ advisers.

These share classes serve to bundle financial adviser

services with the services that funds provide.

Another service that varies among funds is the size

of the investor account that a fund will accommodate.

Funds that offer low account minimums must hire

more staff and devote more resources to service the

additional shareholders than do similarly sized funds

with fewer investors and larger account balances.

Consequently, funds that make investing more

accessible by offering low initial minimums often

have higher expenses than funds that have larger

average accounts

Pressure to Compete on Cost. Although

shareholders purchase funds for performance and

service, they also are heavily invested in lowercost

funds. Investors hold most of their stock and

bond fund assets in funds charging below-average

operational and management expenses (Figure 6).

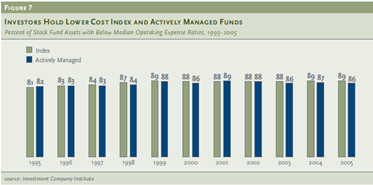

This trend is observable when examining investor

ownership of both index and actively managed

mutual funds (Figure 7).

The demand for lower-cost stock funds seems

particularly notable in recent years. About 90 percent of

the net “new cash” fl owing into stock funds since 2003

went to funds with costs lower than the median fund,

compared with 75 percent of the flows to funds below

the median in the mid-1990s.

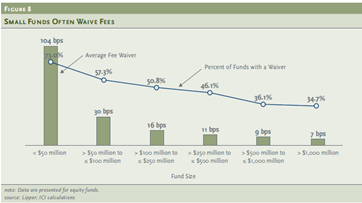

The use of fee waivers to attract and retain

investors provides further evidence that funds compete

on cost. Small funds tend to have higher operational

costs, when measured as a percentage of assets, than

larger funds. This largely occurs because funds often

experience operational efficiencies as they grow in size,

helping to keep costs down. Small funds’ expenses

typically do not reflect their full operational costs

because many small funds waive a portion of their fees

in order to compete with the larger funds (Figure 8). If

competitive market forces were not at play, these small

funds would not have to waive fees and could charge

the level of fees necessary to operate the fund and

provide a profi t to the fund sponsor.

Conclusion

Hundreds of fund sponsors compete aggressively

for investors’ business. No mutual fund sponsor

has a guaranteed base of investors because mutual

fund investors can move their assets at any time to

another fund or a competing product. In this dynamic

marketplace, fund sponsors must continually strive

to deliver performance and service at a competitive

level of fees to their shareholders. These forces, along

with the widely available information about funds

that investors and their financial advisers use to

compare funds, provide a strong market discipline to

organizations that sponsor funds.

Notes

- For example, see Diane Del Guercio and Paula Tkac, “Star

Power: The Effect of Morning star Ratings on Mutual Fund

Flows,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper, 2001–

15, August 2001; Erik R. Sirri and Peter Tufano, “Costly Search and Mutual Fund Flows,” Journal of Finance, 53, 1589–1622; and Judith Chevalier and Glenn Ellison, “Risk Taking by

Mutual Funds as a Response to Incentives,” Journal of Political

Economy, 105, 1167–1200. - Funds were ranked within their CRSP investment categories.

The investment categories used to rank funds by performance

were asset allocation, domestic equity, global equity, global

fixed income, domestic tax-exempt fixed-income, and domestic taxable fixed-income. - Many services that major fund companies now offer were not

available in 1990. Investor statements now list holdings of

outside funds, benchmarks, cost basis, portfolio summary, and personal returns, none of which were offered in 1990. Newer services now available through phone service representatives include balance information, ability to conduct exchanges and redemptions, make address changes, and make direct deposits and payments. Automated phone services now provide transaction history, balances, and the ability to conduct exchanges and redemptions and order tax forms and additional

statements.

No comments:

Post a Comment